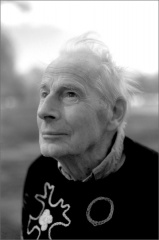

IHT – Arne Næss, a Norwegian philosopher whose ideas about promoting an intimate and all-embracing relationship between the earth and the human species inspired environmentalists and Green political activists around the world, died Monday. He was 96. His editor, Erling Kagge, confirmed his death to Agence France-Presse.

In the early 1970s, after three decades teaching philosophy at the University of Oslo, Næss (pronounced Ness), an enthusiastic mountain climber and an admirer of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” threw himself into environmental work and developed a theory that he called deep ecology. Its central tenet is the belief that all living beings have their own value and therefore, as Naess once put it, “need protection against the destruction of billions of humans.”

Deep ecology, which called for population reduction, soft technology and non-interference in the natural world, was eagerly taken up by environmentalists impatient with shallow ecology — another of Næss’s coinages — which did not confront technology and economic growth.

It formed part of a broader personal philosophy that Naess called ecosophy T, “a philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium” that human beings can comprehend by expanding their narrow concept of self to embrace the entire planetary ecosystem. The term fused “ecological” and “philosophy.” The T stood for Tvergastein, his name for the mountain cabin he built in 1937 in southern Norway, where he often wrote.

Arne Dekke Eide Næss was born in Slemdal, near Oslo, in 1912. His older brother was the shipping tycoon Erling Næss, who died in 1993. After earning a degree from the University of Oslo in 1933 Arne Naess continued his education in Paris and in Vienna, where he became part of the Vienna Circle, a philosophical school dedicated to empiricism and logical analysis. In the belief that philosophers should be self-aware, he also underwent psychoanalysis.

After completing “Knowledge and Scientific Behavior,” his dissertation, in German, he was given a teaching position at the University of Oslo, where, as Norway’s only professor of philosophy until 1954, he was the animating figure in the Oslo School. Working in teams, the Oslo School’s adherents used questionnaires to investigate the meanings that ordinary people assigned to terms like “truth,” “free enterprise” and “democracy.” In 1958 he founded the journal Inquiry.

Over his career, Næss progressed from a radical empiricism to pluralism and skepticism. In his many publications, he took on a wide variety of philosophical problems. Harold Glasser, the editor of “The Selected Works of Arne Næss” (2005), has called him “the philosophical equivalent of a hunter-gatherer.” He was interested in language, meaning and communication, a subject he wrote about in “Interpretation and Preciseness” (1953) and “Communication and Argument” (1966), and in the relationship between reason and feeling. He also wrote books on two thinkers central to his worldview, Spinoza and Gandhi.

In 1969 Naess left the university to develop his ecological ideas, which, he believed, demanded political action. With other environmentalists, he chained himself to rocks in front of the Mardal waterfall, successfully pressing the Norwegian government to abandon plans for a dam on the fjord that feeds the falls. He also wrote extensively on the ethics of mountaineering, a field in which he had considerable expertise. In 1950 he led the first expedition to climb Tirich Mir, a 25,000-foot peak in the Hindu Kush in Pakistan.

His ideas on ecology and ecosophy were developed in numerous books and articles, notably “Freedom, Emotion and Self-Subsistence” (1975), “Ecology, Community and Lifestyle” (1989) and “Life’s Philosophy: Reason and Feeling in a Deeper World” (2002).

Surveying the continuing destruction of the environment, Naess was pessimistic about the 21st century but optimistic about the 23rd. By then, he predicted, population control would show results, technology would be noninvasive and children would grow up in a natural environment. At that point, he said, “we are back in the direction of paradise.”