In his much celebrated play,

Accidental Death of an Anarchist, Italian absurdist Dario Fo brings forth a tragicomic picture of the scandal and its most typical aftermaths in democratic societies, thus described by the main protagonist, the Maniac:

People can let off steam, get angry, shudder at the thought of it… ‘Who do these politicians think they are?’ ‘Scumbag generals!’ […] And they get more and more angry, and then, burp! A little liberatory burp to relieve their social indigestion.

These words came to mind last month when Iceland’s media reported upon the current situation of river Lagarfljót in the east of Iceland. “Lagarfljót is dead,” some of them even stated, citing the words of author and environmentalist Andri Snær Magnason regarding a revelation of the fact that the river’s ecosystem has literally been killed by the the gigantic Kárahnjúkar Dams. The dams were built in Iceland’s eastern highlands in the years between 2002 and 2006, solely to provide electricity for aluminium giant and arms producer Alcoa’s smelter in the eastern municipality of Reyðarfjörður.

The revelation of Lagarfljót’s current situation originates in a report made by Landsvirkjun, Iceland’s state owned energy company and owner of the 690 MW Kárahnjúkar power plant, the main conclusions of which were made public last month. Although covered as breaking news and somewhat of a scandal, this particular revelation can hardly be considered as surprising news.

Quite the contrary, environmentalists and scientists have repeatedly pointed out the mega-project’s devastating irreversible environmental impacts — in addition to the social and economical ones of course — and have, in fact, done so ever since the plan was brought onto the drawing tables to begin with. Such warnings, however, were systematically silenced by Iceland’s authorities and dismissed as “political rather than scientific”, propaganda against progress and opposition to “green energy” — only to be proven right time and time again during the last half a decade.

AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS SHOULD RECEIVE MORE ATTENTION

One of the Kárahnjúkar plant’s functions depends on diverting glacial river Jökulsá á Dal into another glacial river Jökulsá í Fljótsdal, the latter of which feeds Lagarfljót. This means that huge amounts of glacial turbidity are funnelled into the river, quantitatively heretofore unknown in Lagarfljót. This has, in return, led to the disintegration of Lagarfljót’s ecosystem, gargantuan land erosion on the banks of the river, serious decrease in fish population and parallel negative impacts on the area’s bird life.

As reported by Saving Iceland in late 2011, when the dams impacts on Lagarfljót had become a subject matter of Iceland’s media, the glacial turbidity has severely altered Lagarfljót’s colour. Therefore, sunlight doesn’t reach deep enough into the water, bringing about a decrease of photosynthesis — the fundamental basis for organic production — and thereby a systematic reduction of nourishment for the fish population. Recent research conducted by Iceland’s Institute of Freshwater Fisheries show that in the area around Egilsstaðir, a municipality located on the banks of Lagarfljót, the river’s visibility is currently less than 20cm deep compared to 60cm before the dams were constructed. As a result of this, not only is there less fish in the river — the size of the fish has also seen a serious decrease.

Following last month’s revelation, ichthyologist Guðni Guðbergsson at the Institute of Freshwater Fisheries, highlighted in an interview with RÚV (Iceland’s National Broadcasting Service) that the destruction of Lagarfljót’s ecosystem had certainly been foreseen and repeatedly pointed out. He also maintained that aquatic environment tends to be kept out of the discourse on hydro dams. “People see what is aboveground, they see vegetation, soil erosion and drift,” he stated, “but when it comes to aquatic ecosystems, people don’t seem to see it very clearly. This biosphere should receive more attention.”

BENDING ALL THE RULES

All of the above-mentioned had been warned of before the dams construction took place, most importantly in a

2001 ruling by Skipulagsstofnun (Iceland’s National Planning Agency) which, after reviewing the Kárahnjúkar plant’s Environmental Impact Assessment, concluded that “the development would result in great hydrological changes, which would have an effect, for example, on the groundwater level in low-lying areas adjacent to Jökulsá í Fljótsdal and Lagarfljót, which in turn would have an impact on vegetation, bird-life and agriculture.” The impacts on Lagarfljót being only one of the dams numerous all-too-obvious negative impacts, Skipulagsstofnun opposed the project as a whole “on grounds of its considerable impact on the environment and the unsatisfactory information presented regarding individual parts of the project and its consequences for the environment.”

However, Iceland’s then Minister of the Environment, Siv Friðleifsdóttir, notoriously overturned the agency’s ruling and permitted the construction. Although her act of overturning her own agency’s ruling is certainly a unique one, it was nevertheless fully harmonious with the mega-project’s overall modus operandi: For instance, during Alcoa and the Icelandic government’s signature ceremony in 2003, Friðrik Sophusson, then director of Landsvirkjun, and Valgerður Sverrisdóttir, then Minister of Industry, boasted of “bending all the rules, just for this project” while speaking to the US ambassador in Iceland.

A BIOLOGICAL WONDER TURNED INTO DESERT

As already mentioned, the destruction of Lagarfljót is only one of the dams irreversible impacts on the whole North-East part of Iceland, the most densely vegetated area north of Vatnajökull — the world’s largest non-arctic glacier — and one of the few regions in Iceland where soil and vegetation were more or less intact. Altogether, the project affects 3,000 square km of land, no less than 3% of Iceland’s total landmass, extending from the edge of Vatnajökull to the estuary of the Héraðsflói glacial river.

Sixty major waterfalls were destroyed and innumerable unique geological formations drowned, not to forget Kringilsárrani — the calving ground of a third of Iceland’s reindeer population — which was partly drowned and devastated in full by the project. In 1975, Kringilsárrani had been officially declared as protected but in order to enable the Kárahnjúkar dams and the 57 km2 Hálslón reservoir, Siv Fiðleifsdóttir decided to reduce the reserve by one fourth in 2003. When criticized for this infamous act, Siv stated that “although some place is declared protected, it doesn’t mean that it will be protected forever.”

The dams have also blocked silt emissions of the two aforementioned glacial rivers, Jökulsá á Dal and Jökulsá í Fljótsdal, resulting in the receding of the combined delta of the two rivers — destroying a unique nature habitat in the delta. In their

2003 article, published in World Birdwatch, ornithologists Einar Þorleifsson and Jóhann Óli Hilmarsson outlined another problem of great importance:

All glacier rivers are heavy with sediments, and the two rivers are muddy brown in summer and carry huge amounts of sediment, both glacial mud and sand. The Jökulsá á Dal river is exceptional in the way that it carries on average 13 times more sediment than any other Icelandic river, 10 million metric tons per year and during glacial surges the amount is many times more. When the river has been dammed this sediment will mostly settle in the reservoir.

In contravention of the claim that Kárahnjúkar’s hydro electricity is a “green and renewable energy source,” it is estimated that the reservoir will silt up in between forty and eighty years, turning this once most biologically diverse regions of the Icelandic highlands into a desert. While this destruction is slowly but systematically taking place, the dry dusty silt banks caused by the reservoir’s fluctuating water levels are already causing dust storms affecting the vegetation of over 3000 sq km, as explained in Einar and Jóhann’s article:

The reservoir will be filled with water in autumn but in spring 2/3 of the lake bottom are dry and the prevailing warm mountain wind will blow from the south-west, taking the light dry glacial sediment mud in the air and causing considerable problems for the vegetation in the highlands and for the people in the farmlands located in the valleys. To add to the problem the 120 km of mostly dry riverbed of Jökulsá á Dal will only have water in the autumn, leaving the mud to be blown by the wind in spring.

This development is already so severe that residents of the Eastfjords municipality Stöðvafjörður, with whom Saving Iceland recently spoke, stated that the wind-blown dust has been of such a great deal during the summers that they have often been unable to see the sky clearly.

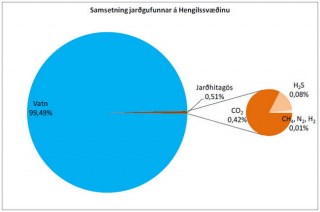

All of the above-mentioned is only a part of the Kárahnjúkar dams over-all impacts, about which one can read thoroughly here. Among other factors that should not be forgotten in terms of hydro power would be the dams’ often underestimated contribution to global warming — for instance via reservoirs’ production of CO2 and methane (see here and here) — as well as glacial rivers’ important role in reducing pollution on earth by binding gases that cause global warming, and how mega-dams inhibit this function by hindering the rivers’ carrying of sediments out to sea.

TEXTBOOK EXAMPLE OF CORRUPTION AND ABUSE OF POWER

“Lagarfljót wasn’t destroyed by accident,” Andri Snær Magnason also said after the recent revelation, but rather “consciously destroyed by corrupt politicians who didn’t respect society’s rules, disregarded professional processes, and couldn’t tolerate informed discussion.” The same can, of course, be said about the Kárahnjúkar ecological, social and economical disaster as a whole, the process of which was one huge textbook example of corruption and abuse of power.

Responding to same news, Svandís Svavarsdóttir, Iceland’s current Minister of the Environment, cited a recent report by the European Environment Agency, titled “Late Lessons from Early Warnings,” in which the results of a major research project into mega-project’s environmental impacts and public discussion are published. One of the damning results, the report states, is that in 84 out of 88 instances included in the research, early warnings of negative impacts on the environment and public health proved to be correct.

This was certainly the case in Iceland where environmentalists and scientists who warned of all those foreseeable impacts, both before and during the construction, found themselves silenced and dismissed by the authorities who systematically attempted to suppress any opposition and keep their plans unaltered.

One of the most notorious examples of this took place after the publication of Susan DeMuth’s highly informative article,

“Power Driven,” printed in The Guardian in 2003, in which she highlighted all the up-front disastrous impacts of the project. The reaction in Iceland was mixed: While the article served as a great gift to Icelandic environmentalists’ struggle — tour guide Lára Hanna Einarsdóttir suggesting “that an Icelandic journalist would have lost their job if he or she had been so outspoken” — the reaction of the project’s prime movers was one of fury and hysteria. Mike Baltzell, president of Alcoa Primary Development and one of the company’s main negotiators in Iceland, wrote to The Guardian accusing DeMuth of “creating a number of misconceptions” regarding the company’s forthcoming smelter. Iceland’s Ambassador in the UK and Landsvirkjun’s Sophusson took a step further, contacting the British newspaper in a complaint about the article’s content and offering the editor to send another journalist to Iceland in order to get “the real story” — an offer to which the paper never even bothered to reply.

Another example is that of Grímur Björnsson, geophysicist working at Reykjavík Energy at that time, who was forbidden from revealing his findings, which were suppressed and kept from parliament because they showed the Kárahnjúkar dams to be unsafe. His 2002 report, highly critical of the dams, was stamped as confidential by his superior at the time. Valgerður Sverrisdóttir, then Minister of Industry, subsequently failed to reveal the details of the report to parliament before parliamentarians voted on the dams, as she was legally obliged to do. Adding insult to injury, Grímur was finally deprived of his freedom of expression when his superior at Reykjavík Energy — taking sides with Landsvirkjun — prohibited him to speak officially about the Kárahnjúkar dams without permission from the latter company’s director at that time, Friðrik Sophusson.

THE SHADOW OF POLLUTED MINDS

Similar methods applied to the East-fjords and other communities close to the dams and the smelter, where the project’s opponents were systematically ridiculed, terrorized and threatened. One of them is Þórhallur Þorsteinsson who, in a

thorough interview with newspaper DV last spring, described how he and other environmentalists from the East were persecuted for their opposition to the dams. In an attempt to get him fired from his job, politicians from the region even called his supervisor at the State Electric Power Works, for which he worked at the time, complaining about his active and vocal opposition. Another environmentalist, elementary school teacher Karen Egilsdóttir, had to put up with parents calling her school’s headmaster, demanding that their kids would be exempt from attending her classes.

Farmer Guðmundur Beck — described by DeMuth as “the lone voice of resistance in Reyðarfjörður” — was also harassed because of his outspoken opposition towards the dams and the smelter. After spending his first 57 years on his family’s farm where he raised chicken and sheep, he was forced to close down the farm after he was banned from grazing his sheep and 18 electricity pylons were built across his land. Moreover, he was literally ostracised from Reyðarfjörður where Alcoa’s presence had altered society in a way thus described by Guðundur at Saving Iceland’s 2007 international conference:

In the East-fjords, we used to have self-sustaining communities that have now been destroyed and converted into places attracting gold diggers. Around the smelter, there will now be a community where nobody can live, work or feed themselves without bowing down for “Alcoa Director” Mr. Tómas.* — We live in the shadow of polluted minds.

(*Mr. Tómas” is Tómas Már Sigurðsson, Managing Director of Alcoa Fjarðaál at that time but currently president of Alcoa’s European Region and Global Primary Products Europe. Read Guðmundur’s whole speech in the second issue of Saving Iceland’s Voices of the Wilderness magazine.)

A LESSON TO LEARN?

All of this leads us to the fact that Icelandic energy companies are now planning to go ahead and construct a number of large-scale power plants — most of them located in highly sensitive geothermal areas — despite a seemingly non-stop tsunami of revelations regarding the negative environmental and public health impacts of already operating geothermal plants of such size. This would, as

thoroughly outlined by Saving Iceland, lead to the literal ecocide of highly unique geothermal fields in the Reykjanes peninsula as well as in North Iceland.

Two of the latter areas are Þeistareykir and Bjarnarflag, not far from river Laxá and lake Mývatn, where Landsvirkjun wants to build power plants to provide energy to heavy industry projects in the north. Large-scale geothermal exploitation at Hellisheiði, south-west Iceland, has already proven to be disastrous for the environment, creating thousands of earthquakes and a number of polluted effluent water lagoons. The Hellisheiði plant has also spread enormous amounts of sulphide pollution over the nearby town of Hveragerði and the capital area of Reykjavík, leading to an increase in the purchasing of asthma medicine. Another geothermal plant, Nesjavallavirkjun, has had just as grave impacts, leading for instance to the partial biological death of lake Þingvallavatn, into which affluent water from the plant has been pumped.

Responding to criticism, Landsvirkjun has claimed that the Bjarnarflag plant’s effluent water will be pumped down below lake Mývatn’s ground water streams. However, the company has resisted answering critical questions regarding how they plan to avoid all the possible problems — similar to those at Hellisheiði and Nesjavellir — which might occur because of the pumping and thus impact the ecosystem of Mývatn and its neighbouring environment. In view of this, some have suggested that Iceland’s next man made ecological disaster will be manifested in a headline similar to last month’s one — this time stating that “Mývatn is dead!”

Concluding the current Lagarfljót scandal — only one manifestation of the foreseen and systematically warned of Kárahnjúkar scandal — the remaining question must be: Will Icelanders learn a lesson from this textbook example of political corruption and abuse of power?

Recent polls regarding the coming parliament elections on April 27, suggests that the answer is negative as the heavy-industry-friendly Framsóknarflokkur (The Progressive Party), for which both Siv Friðleifsdóttir and Valgerður Sverrisdóttir sat in parliament, seems to be about to get into power again after being all but voted out of parliament in the 2007 elections. Following the Progressives, the right-wing conservative Sjálfstæðisflokkur (The Independence Party) is currently the second biggest party, meaning that a right-wing government, supportive of — and in fact highly interrelated to — the aluminium and energy industries, is likely to come into office in only a few days from now.

In such a case, Iceland will be landed with the very same government that was responsible for the Kárahnjúkar disaster as well as so many other political maleficences, including the financial hazardousness that lead to the 2008 economic collapse and Iceland’s support of the invasion in Iraq — only with new heads standing out of the same old suits. Sadly but truly, this would fit perfectly with the words of Dario Fo’s Maniac when he states on behalf of the establishment:

Let the scandal come, because on the basis of that scandal a more durable power of the state will be founded!