On May 18, Icelandic newspaper DV published an interview with Janne Sigurðsson, director of Alcoa Fjarðaál since the beginning of this year. In the interview, Janne describes, amongst other things, crisis meetings that were held within the company due to the protests against the construction of the Kárahnjúkar dams and the aluminium smelter in Reyðarfjörður. With gross and incongruous sentimentality she compares the society in Eastern Iceland, during the time of the construction, with a dying grandmother, whose cure is fought against by the anti-Alcoa protesters. Janne also maintains — and is conveniently not asked to provide the factual backup — that only five people from the East were opposed to these constructions.

On May 21, however, DV published an interview with Þórhallur Þorsteinsson, one of the people from Eastern Iceland who had the courage to oppose the construction. In the interview, which turns Janne’s claims upside down, it emerges how heavy the oppression was in the East during the preamble and the building of the dams and smelter was — people where “oppressed into obedience” as Þórhallur phrases it. He talks about his experience, loss of friends, murder threats, the attempts of influential people to dispel him from his work, and the way the Icelandic police — and the national church — dealt with the protest camps organized by Saving Iceland, which lead him to wonder if he actually lived in a police state.

Þórhallur Þorsteinsson is one of the people from Eastern Iceland who protested against the construction of the Kárahnjúkar dams. For that sake, he was bandied about as an “environmentalist traitor”, accused of standing in the way of the progress of society. Influential people attempted to dispel him from his job, he had to answer for his opinions in front of his employers, and his friends turned against him. The preparations for the construction started in 1999, but the construction itself started in 2002. The power plant started operating in 2007 but the wounds have not healed though a few years have passed since the conflict reached its climax.

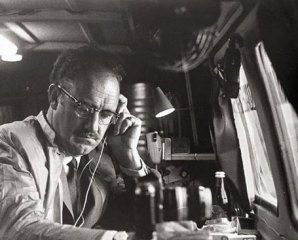

“There are certain homes here in Egilsstaðir that I do not enter due to the conflict. Before, I used to visit these homes once or twice a week. I am not sure if I would be welcome there today. Maybe. But in these homes I was, without grounds, hurt so badly that I have no reason to go there again. Now I greet these people but I have no reason to enter their homes. I was virtually persecuted,” Þórhallur says, sitting in an armchair in his home in Egilsstaðir.

His home bears strong signs for his love of nature, his bookshelves are filled with books about the Icelandic highlands, nature and animals. For decades, Þórhallur has travelled in the highlands and did thus know this area [the land destroyed by the Kárahnjúkar dams] better than most people. “I had been travelling in this area for decades. I had gone there hiking and driving and I have also flown over it. I went there in winters just as in the summers. I went there as a guide and I knew the area very well. So I am not one of those who just speak about this area but have never got to know it.”

Not only did he know the land but also cared for it. He was hurt to see it drowned by the reservoir and has never managed to accept its destruction. “I am immensely unhappy with everything regarding this project. The dams, the [Alcoa] aluminium smelter, the environmental impacts, and additionally, it has not brought us what was expected. Thus I find hardly anything positive about this,” Þórhallur says.

“The sacrifice of this part of the highlands, the environmental impacts of these constructions, just can not be justified. Waterfalls by the dozen, many of them extremely beautiful, are rapidly disappearing and are just about waterless. A highly remarkable land went under water, under the reservoir, for instance Hálsinn which was the main breeding ground for reindeer. Additionally, this was the only place in Iceland with continuous vegetation from the sea, all the way up to the glacier. This has now be interrupted by Hálslón [the reservoir].”

The Resistance in the East

During the journalist’s trip around Eastern Iceland, many of the locals spoke a lot about how artists from 101 Reykjavík [the center of the city] protested against the construction. Þórhallur, however, points out that the original resistance against the project was formed in the local region. “People tend to forget this fact all the time, as they only speak about 101 Reykjavík. Before the conflict started, an association for the protection of Eastern Iceland’s highlands was founded here. It was founded with the purpose of opposing the construction — Kárahnjúkar had not even entered public discussion at that point although we, of course, knew about it.”

About thirty people joined the inaugural meeting and agreed upon the importance of such an association. Soon, a few people left the organization. “Those who had an opposite opinion compared to what people generally thought about the project were oppressed. The picture was painted in a way suggesting that the residents of Eastern Iceland should stand together. The rest of us, who were against the project, were not considered true members of this society. And we were not good citizens at all. In people’s minds, we were traitors. We were the people who wanted to send people back to the turf huts, as they used to say. We were said to be against development, against creating a good future for our children. All this was thrown at us, that the children would not come back home after studying, that they would not get any jobs. By opposing the construction, I was, in these people’s minds, taking away their children’s future livelihood, preventing the creation of jobs, and lowering real estate prices here in the east. I got to hear all of this. This is how it was.”

The First Protests

At a certain point, the verbal abuse was taken further than can be considered normal. “My life was threatened. A man that I used to work with met me in the street and said that I ought to be shot. Of course, it was painful to live through this, it hurt because they were trying to oppress me. They personified the issue so they could portray me as if I was taking something away from people, as if I was preventing the people here from living an ordinary life. This was the attitude.

I have lived here since I was a little kid and from early age I have been contributing to this community. I have partaken in building it up, socially and as an individual. I have been here all my life. Despite my opposition to this construction, I did not consider myself being any less of a member of this community. Nothing of what I have done justifies the accusations of me wanting to ruin this community. I was simply against this construction. But just like others, I was to be suppressed into obedience.”

Despite all this, Þórhallur refused to throw away his ideals and stay silent. Determined not to be silenced, he continued his fight with both words and actions. “I am probably the only resident in Eastern Iceland who ever has been fined for opposing the Kárahnjúkar dams [in fact Gudmundur Mar Beck, farmer at Kollaleyra in Reydarfjordur (site of the ALCOA smelter) was also fined a hefty sum for protesting against the project. Ed. SI.org]. Along with others, I blockaded a bridge over river Besstastaðaá and was fined,” he says and adds that he did happily pay the fine. “This action was symbolic for the situation at that time, as a token of the fact that the case had become insolvable. We didn’t intend to completely prevent these people from continuing their way,” Þórhallur says. These people were the board of Landsvirkjun [Iceland’s national energy company] as well as Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, then mayor of Reykjavík [later Minister for Foreign Affairs in the government that was toppled by protesters during the winter of 2008-9], and the area that was at stake at that time was Eyjabakkar wetlands. “We read two statements out loud, from the Association for the Protection of Eastern Iceland’s Highlands, and after that the protest was over.”

He does not regret this, even though he had to face the consequences his actions. “I was there in my spare time but at this time I worked for the The State Electric Power Works. Following the protest, we witnessed one of the worst witch-hunting periods in the history of Eastern Iceland. The severity is very memorable to me.”

Harsh Attacks

This protest had been organized by Þórhallur as well as Karen Egilsdóttir, who was an elementary school teacher, and Hrafnkell A. Jónsson, who has now passed away. “Parents phoned the school’s headmaster and demanded that their kids would not have to go to her classes. Politicians in the East systematically tried to get me fired from my job. They phoned both the State’s and the Region’s electric utility directors, demanding that I would be fired because of a thing I did in my spare time. These same men constantly interrupted the Chairman of RARIK [Iceland State Electricity] and I had to stand up for my opinions. I had to show up in front of the Region’s electric utility director and proof that I had been at the protest during my spare time. And as my words were not enough, I had to get my supervisor to come and proof it. Everything was tried. It was harsh.

And when I was informed that very influential people in the East, respected members of their society, were trying to get back at me and get me dispelled from work because of my opinions, I got a very strange feeling regarding what kind of a society I live in.

I also witnessed the behaviour of the police who chased protesters around the highlands, which made me wonder if I lived in a police state. The police tried to prevent protesters from resting by putting wailing sirens on during the middle of the nights, they constantly drove past them and around their cars, took photographs during darkness using flash, and blocked roads so that people could not bring them food. I saw all of this taking place.”

Always Knew of More Opponents

For two years in a row, the protesters set up camps in the highlands. During the first summer [2005], the protest camp was pitched on a land owned by the Bishop’s Office. “The church’s tolerance was not greater than so that the Bishop’s Office asked for the protesters to be removed. The second year I brought them food by taking an alternate route to their camp when the police had closed the main road. I supported these people because they were doing a job that many of us here, the locals, could not do. They were protesting against something that very few people from the East felt up to, due to the way those who dared to protest were treated. We were monitored and the word, about what kind of a people we were, was spread around. That is the reason why many people contacted me, people who otherwise did not dare to voice their opinion, did not dare to join the struggle. I always knew that I spoke on behalf of more people than just myself.”

Thus, when Saving Iceland contacted Þórhallur, he was more than willing to help. He was a spokesperson of the Icelandic Touring Association and explained to Saving Iceland that it would be just about impossible to expel them from the camping area at Snæfell, which had been open to the public for many decades. Eventually, a ten days long camp was to be set up there. “Then the word started to spread and I received a phone call from the Bishop’s Office, asking me if we could stop the camp from taking place. I told them that this camping area had been open to the public ever since the hut was built, but I invited them to come to the East and try to expel them themselves. A few days later, Landsvirkjun’s public relation manager called me and brought up the same thing. He asked about the possibility of putting a limit on the amount of people allowed to stay at the camp, if the health and safety authorities would agree upon this amount of people, etc. etc. I told him the same: “This is an open camping area and we do not choose who gets to stay and who not.” You get the picture of how the situation was at this time.”

Not everybody was happy within the Touring Association. “Some of the board members were against it and conflicts took place within the association. I asked them what they intended to do, if the Association would then, in the future, pick out people allowed onto the camping areas. I said to them: These people just enter the camping area, follow the current rules and pay their fee. While so, we can not do anything. Then, some of the people realized how far they had stepped over limits.

So the protesters came to Snæfell and stayed for ten days. That worked out pretty well but then they went to other places [within the intended reservoir. Ed. SI] and came up against all sorts of misfortunes.”

A Protection Cancelled

He also points out how politicians behaved in the Kárahnjúkar issue. “It is interesting to look at the current discussion about the Energy Master Plan. Some people now say that politicians are interfering with specialists’ work. In that case, it is worth remembering the fact that the Kárahnjúkar dams were removed from the Master Plan and were only briefly considered in that context. Those who decided this were politicians. The project underwent an Environmental Impact Assessment and Iceland’s Planning Agency rejected it due to the drastic and irreversible environmental impacts. But then the case was simply taken into a political process and soon it was decided to go ahead and build the dams, despite the Planning Agency’s view that the environmental impacts were unacceptable.

The way this case was handled should actually be an ample reason for an investigation. This area’s official protection was cancelled so the land could be drowned. Never before had this happened in Iceland, but it was nevertheless done by Siv Fiðleifsdóttir, then Minister of the Environment. That is her monument: being the one Minister of the Environment, responsible for the most severe environmental destruction,” Þórhallur says plain-spoken.

The Old People Got Away

He believes that only the further damming of Þjórsárver wetlands would have been a even bigger environmental sacrifice. “Thereafter came Kárahnjúkar. But this is all about politics, Icelanders have no time for politics. The Danes have done fine without heavy industry. This is always just a question of a political policy, and for decades, the inhabitants of Reyðarfjörður [where the Alcoa smelter is located] have been promised that someone will come and do something for them. In such a position, people tend to forget their survival instinct.

The exchange rate was way too high and all the local fishing industry left. Fishing company Skinney Þinganes moved all their business to Höfn in Hornafjörður, while Samherji [another seafood company incidentally owned by the family of Halldor Asgrimsson, one of two main perpetrators of the Karahnjukar dams] bought fishing quota from Stöðvarfjörður and Eskifjörður and took it away from there. But because an aluminium smelter was on its way, people believed that this was no problem. It is always possible to starve people into obedience. It is easy to change the mentality in such a way that it simply receives. All of a sudden the smelter appeared as some sort of a life buoy. The positive side of it is that now there are much younger people living in Fjarðabyggð [combined municipality of a few towns, including Reyðafjörður] than before. The old people got away. But behind this is the sacrifice. The sacrifice was too big and it was the whole region’s sacrifice. We sacrificed this for the benefits of a North American corporation. We sacrificed everything for too little. While all this took place, people were supposed to stand together and they spoke about the region as a totality. But immediately as the construction was over, all such solidarity disappeared.”

Direct and Indirect Payments

He is, nevertheless, able to understand why the region’s people were in favour of the construction and focused on getting a smelter. “I understand them very well, as they got something out of it. But it is clear that we got too little. 200 people from here work in the smelter, I think. 200 jobs — that is not enough for such a sacrifice. 500 jobs would also not have been enough when compared with the land that was destroyed. But people can be bought up if they are handed money. And I understand farmers who had never seen any real money but were all of sudden promised amounts which they would, in any other case, not have been able to even dream of. But is that the way we want it to be? That people can be mislead by money?

If they would have stood their ground and rejected all of , if the Fljótsdalshérað region would have rejected this, and the local politicians and the public — then this would never have become true. Now, some people state that we never had anything to say about it, but these are people who have a bad conscience because they did not fight against the construction.

Everywhere in the world, except Iceland, these “counterbalance steps” as they are called, would have been considered bribery. Basically, local politicians were bought up. Farmers and influential people were hired on good salaries and farmers got fertilizer to use on uncultivated land. All such indirect payments to influential people certainly have an impact on what decisions are made and on what premises they are made. Some farmers received compensation due to the destruction, but to pay compensation to only one generation is not acceptable. It would have made much more sense to link the compensation with the power plant’s electricity production and pay them to those living in the area on an annual basis.”

Gullfoss Falls Could be Forgotten

Asked about the actual value of the land now lost, Þórhallur answers: “This land used to be an attraction. The waterfalls that have now dried up, the vegetated land that went under water, the wilderness which is becoming increasingly precious. Being able to live with such quality is like nothing else. If well organized, hundreds of thousands of travellers could have been been shown this land without the land being harmed. Seen from a long-term perspective, that could have created more money than the dams.”

Think about the fact that the Gullfoss waterfalls and the hot spring Geysir did not use to be popular tourist places. It was not easy to get to them, say fifty or hundred years ago. We can not sacrifice something just because only a few people know about it. Using that same argument, we could as well dry up Gullfoss, as in a few decades we would forget about it and the next generations would not know what a beautiful waterfall used to flow there. We can not think in that way. One generation can not treat Iceland’s nature, this national treasure, in such a way.

I first drove to Hafrahvammar canyon in 1972 and, in fact, roads and paths have been there for many decades, but they were quite difficult to pass. That could easily have been changed and thus, the access to the area could have been increased.”

“The Same Horrific Situation Far and Wide”

In the end he says that the aluminium smelter has not lived up to society’s expectations. “It still has not been possible to staff the smelter with Icelanders. Only Icelandic-speaking people are hired there but despite all the unemployment and all the advertising, sub-contractors partly staff their companies with foreigners, as Icelanders are not willing to take on these jobs. The labour turnover has been about 25 percent. Despite the fiasco the nation has went through [the 2008 economic collapse], this is not considered a decent option for a working place.

Was the hole purpose of drowning this land, destroying this nature, drying up these waterfalls, to be able to import migratory workers from abroad? Do some of the unemployed people on Suðurnes not want to come to the East, move into all the empty apartments and work in the smelter in Reyðarfjörður? Isn’t there something wrong? Why do people not apply for jobs here?” Þórhallur asks and adds that the pot-rooms and the cast-house are not really desirable workplaces, though some other jobs in the smelter might lure some. “One has to work 12 hours shifts and I know no-one who works in the smelter and looks at it as their future job. I also know people who used to work there but quit because of the long shifts. They did not want to sacrifice their family life for the job. People will work there until they find a better job. If the economy recovers in a few years time, how will this end? Will we end up having to staff the smelter solely with foreign labour on season?

This was supposed to save everything but the same horrific situation is evident far and wide. The smelter had, for instance, no positive impacts in nearby places like Stöðvarfjörður and Breiðdalsvík.

The planned population increase in Eastern Iceland never took place, and as the senselessness was absolute, everything collapsed. No-one lives in the houses that were built — streets were laid but no houses built on them. The municipality is bankrupted, as it is expensive to go into such a construction and to sit up with this half-finished street-system. This situation might recover in a few decades, but it still was not worth it.”